You could be forgiven for thinking McLaren had just thrown away another victory, such has been the reaction from some quarters to the way the team handled the Hungarian Grand Prix.

McLaren has made some high-profile errors this season, most recently at Silverstone two weeks ago where the decision to pit only one of its cars as rain started to fall was already bad enough – massively hurting Oscar Piastri’s race – but then opting against using the medium tire that it had saved compared to its rivals at Lando Norris’ final pit stop ended the hopes of both drivers.

That was a race McLaren arguably should have won, and potentially could have finished one-two, but it did not have a clear pace advantage that weekend. At different phases of the race, Mercedes or Max Verstappen could claim to have quicker cars.

It was a different situation at the Hungaroring, where McLaren looked to have the edge all weekend and duly cemented it with a front-row lock-out. But as recent races had shown, there were no guarantees that would lead to a victory.

I asked Andrea Stella on Saturday night if a one-two finish in the race would be the only result he would be happy with, and the McLaren team principal insisted not, because if nothing else, you can never count out Verstappen from any race. Plus, track position would be crucial in Budapest, so other cars can severely impact your chances.

Fast forward to the start and the three-wide moment that saw Piastri take the lead after getting a better launch than his teammate, and Norris eventually emerging in second place after Verstappen returned the position to him after overtaking off track.

This was a spot from which McLaren had every chance of converting, and it wasn’t going to let it go.

Far from criticizing the call that the team made at the final round of pit stops, it’s Red Bull that had slipped up. Drivers had noted how hard it was to follow other cars through the middle sector – lapping traffic was costing Piastri time – and also how dirty it was off-line, again thanks to a Piastri moment at Turn 11 that halved his advantage over Norris.

So no risks could be taken when it came to track position, and as the second car on the road, Norris was the one under a greater threat. Piastri had more of a buffer to a non-McLaren car, so could afford to be brought into the pits as the second of the two cars for the final pit stops.

A lot of the focus has been on the gap to Lewis Hamilton when Norris emerged from the pits. The margin had been 25.5s starting the lap before Norris’ final stop, and at the pace each was lapping at at that point, it was set to be 24 seconds across the line next time around. Given you need a 20-second advantage to pit and emerge ahead, pitting Piastri first – on the same lap Norris was actually brought in – and leaving Norris out for one more lap would have seen his gap to Hamilton become roughly 22.5s.

That was what the team was paying attention to, because Hamilton and Leclerc had both stopped early – at the end of lap 40 – for that final stint. Why? To undercut Verstappen, because track position was key. And even though the Red Bull was a quicker car than the Mercedes and Ferrari, there were no guarantees he’d be able to overtake once he caught them.

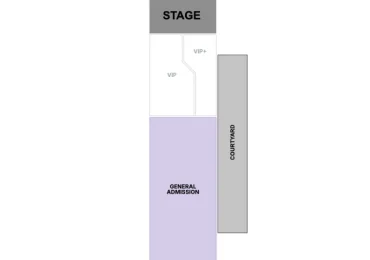

McLaren’s strategy decisions during the Hungarian GP were all geared towards ensuring that the team had maximum protection against outside threats. Andy Hone/Motorsport Images

McLaren’s strategy decisions during the Hungarian GP were all geared towards ensuring that the team had maximum protection against outside threats. Andy Hone/Motorsport Images

The whole scenario is a central part of why Verstappen was so frustrated on team radio, because he was being undercut twice and having to fight to make progress. But he was also one lock-up away from cleanly passing Hamilton for third and potentially closing in on the McLarens ahead.

Verstappen’s pace in clear air – he had a spell lapping over half a second quicker than the leaders once released by Hamilton before his final stop – had not gone unnoticed, so McLaren didn’t want to stop too early in response to Hamilton and Leclerc, handing Verstappen the lead for more laps than was necessary when a well-timed Safety Car would offer him a shorter stop.

Similarly, stop too early with the two McLaren cars and it opens up the potential for Verstappen to get a big enough tire advantage to be a threat if there was a later interruption, too.

So the timing of the final stops had weighed all of that up, and then factored in that if you stopped Piastri first – to avoid an undercut for Norris – then you put Norris more at risk from the closing Hamilton and Leclerc. One stuck wheel and a five-second pit stop rather than the usual two-to-three seconds and he could lose a position or two.

The Norris stop was playing it extremely safe, and locking in a one-two result for the team. The car most at risk was Norris as he was second on the road, so in being allowed to pit first he was actually being prioritized by McLaren, when usually the lead car would expect that.

McLaren then left Piastri out for an extra lap to balance the threat from cars behind with the desire for him to have the best tire life, knowing he would comfortably be jumped by Norris. It had full faith in its driver to adhere to the call to then swap positions back at that point, and was just enjoying the rare luxury of being one-two with two competitive cars in control of a race.

If Norris had instantly slowed to let Piastri by, or done so a few laps into the stint by generally managing his pace more, then none of the increasingly-panicked radio messages would have been required and the team would likely have received universal praise for its handling of the whole situation.

The only reason any controversy was created, was due to Norris’ somewhat understandable hesitancy when he suddenly had a race win in his hands once again. He had been warned upon entry into the pits that it wasn’t a move to undercut Piastri, and was reminded as soon as his team-mate emerged behind him too. But he argued that he could be allowed to keep the extra points to try and fight for the championship, before eventually ceding the place.

Norris could have handled it better, but also showed the selfishness needed to think about his own situation long and hard before doing what the team expected. McLaren, too, could have been more firm and clear with its radio messages around the pit stop and immediately after, rather than a softly-softly approach for a number of laps.

But we’re splitting hairs over the way a team turned a one-two qualifying result into a one-two finish with two competitive drivers who have enjoyed a good relationship, and are a key part of why McLaren is becoming increasingly successful. The constructors’ championship is a realistic possibility, even if the drivers’ remains a long shot.

Criticism of the way McLaren has failed to maximize results in previous races has been justified. Noisy blowback for ensuring it maximized one this time around isn’t, awkward radio messages for a few laps or not.